Farmers and legislators channel rural frustration as they push for tractor Right to Repair

Farmers need software tools to fix their tractors but manufacturers such as John Deere won’t sell them, despite a 2018 agreement

For years, farmers have been calling for access to the tools needed to repair modern tractors, combines and other farm equipment. Their efforts resulted in dozens of Right to Repair bills — legislation that would require manufacturers to give access to their repair materials to customers and independent repair shops.

Responding to that pressure in 2018, trade associations representing the dealers and manufacturers of agricultural equipment — the Association of Equipment Manufacturers (AEM) and the Equipment Dealers Association (EDA) — debuted a new industry promise to create and sell (or lease) new tools to allow farmers to repair their own equipment. These trade associations pledged that the tools would be available for equipment sold on or after January 2021.

But 7 weeks into 2021, these tools are not for sale on JohnDeere.com, and we’d heard reports from farmers across the country their local dealers didn’t have those promised tools available. To investigate, U.S. PIRG Right to Repair Advocate Kevin O’Reilly called 12 John Deere dealerships in 6 different states. Of those, 11 told Kevin that they don’t sell diagnostic software and one gave him the email address of someone to ask for the tools — though after two days, Kevin had not heard back.

Meanwhile, Vice News made a separate set of phone calls to dealerships, with the same results. Reporters asked David Ward, a spokesperson for the AEM, if he could point to a single instance where farmers can purchase software diagnostic tools, but Vice reports that this email was not returned. Vice put its assessment of the position bluntly in the headline: “John Deere Promised Farmers It Would Make Tractors Easy to Repair. It Lied.”

Deere in the Headlights Shows How Critical Software is For Repair

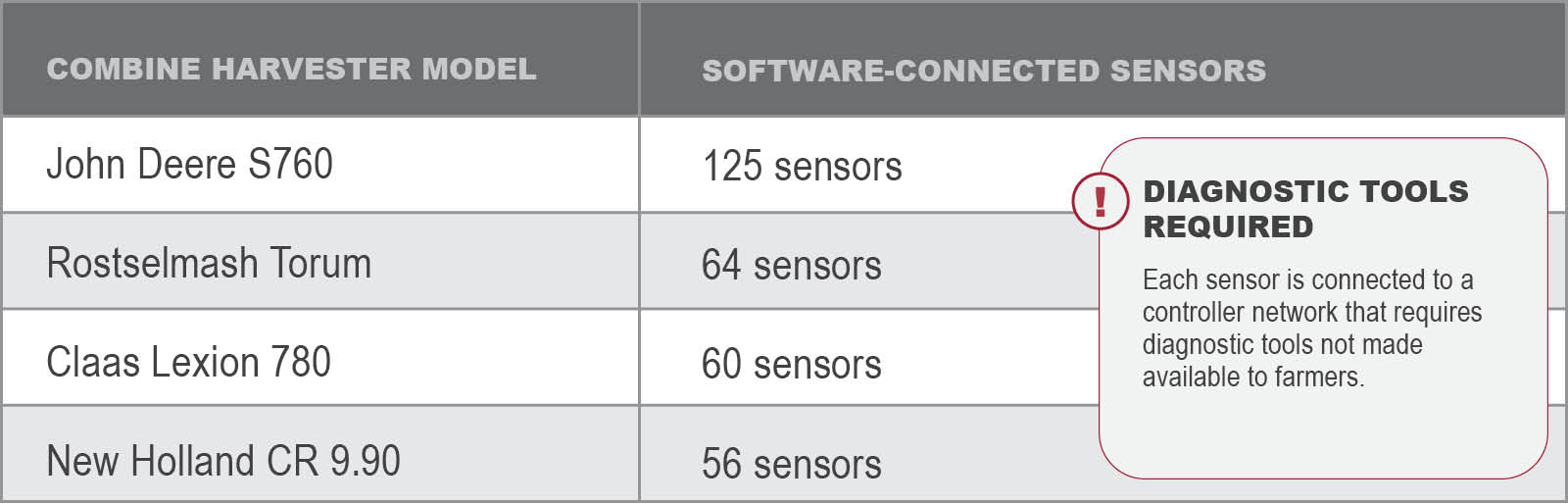

The lack of software repair tools is a huge barrier for farmers, according to a new U.S. PIRG Education Fund report Deere in the Headlights. The report provides background information about why John Deere and its competitors’ tractors are so hard to fix. Modern farm equipment, like most 21st century technology, runs on software. Our research found as many as 125 software-connected sensors in a single combine harvester. If any of those sensors go down, software diagnostic tools are needed to repair the combine and put it back into use.

But when manufacturers restrict access to the software tools needed to repair broken tractors, farmers need to rely on dealerships and a simple task can turn into a month-long wait.

For example, when a tractor belonging to Walter Schweitzer, a third-generation farmer and President of the Montana Farmers Union, broke down, he was forced to take it to the dealer instead of buying $500 in parts and fixing it on his own. A $5,000 repair bill later, he was able to get back to work—but a month behind on the typically tight farming schedule of plowing, planting and harvesting.

“Farmers, we’re an independent bunch. When we see a problem, we’re used to fixing it,” Schweitzer said. “But without the software we need to repair our equipment, we’re serfs. We deserve the freedom to fix our own stuff.”

Legislators Share Why We Need Right to Repair Laws

U.S. PIRG hosted a virtual panel on Thursday to share the findings of the report. Viewers heard from Walter Schweitzer and a bipartisan group of three legislators — Florida State Sen. Jennifer Bradley, Montana State Rep. Katie Sullivan and Missouri State Rep. Barry Hovis — all of whom are sponsoring legislation to grant farmers in their states access to repair tools, parts and documentation.

Sen. Bradley said she heard about the issue on the campaign trail.

“As I went to campaign out across the district in a lot of these rural counties, at my first stop I met with a generational farmer … and this was one of the first issues he raised,” she said.

Sen. Bradley recalled the farmer had a tractor with what appeared to be a bad fuse, but had to load the tractor and travel a long distance, because no authorized shop was nearby, for what turned out to be a very expensive repair.

“That sort of violates your fundamental notion of ownership. You bought it, you should have the ability to take care of it,” Bradley continued.

Rep. Sullivan noted how frequently farmers brought up these issues to her, and how intense the opposition lobbying has been. She understands that dealers and equipment manufacturers are well represented, but the farmers don’t have the voice in the legislature. As an intellectual property lawyer, she is especially frustrated with claims that selling repair tools represents a loss of intellectual property:

“I’m an IP attorney, I’m sensitive to IP rights … no one carrying these bills is looking to … take rights from manufacturers,” said Sullivan.

Rep. Sullivan was most upset that opposition lobbyists have claimed “the farmers that speak to [Rep. Sullivan] are lying,” and only want to modify equipment illegally.

Rep. Barry Hovis, from Whitewater, Missouri, is an active rancher. He has personally been denied the digital tools to repair equipment, and sees it as a downtime issue.

“In Southeast Missouri when harvest season starts …everyone is running multiple combines, everything. [Dealers] only have so many staff,” said Hovis. He went on to say it was unreasonable in these conditions to prevent others from doing repairs.

“You either have an open market for repair, or you don’t,” said O’Reilly. “Given how difficult it is to get your hands on even the non-comprehensive tools said to be available, it’s no wonder that more and more farmers are calling for Right to Repair reforms.”

Topics

Authors

Nathan Proctor

Senior Director, Campaign for the Right to Repair, PIRG

Nathan leads U.S. PIRG’s Right to Repair campaign, working to pass legislation that will prevent companies from blocking consumers’ ability to fix their own electronics. Nathan lives in Arlington, Massachusetts, with his wife and two children.

Find Out More

Oregon (and Google) chooses the Right To Repair

Giving the FTC an earful on Right to Repair

Our 2024 priorities in the states