Is more energy always better? Why pursuit of “energy abundance” risks missing the point

Tapping the abundance of clean energy all around us can free us from a future of calamitous climate change and improve people's lives. But only if that is how we choose to use it.

Abundant, cheap energy, wrote Ezra Klein in a recent New York Times column, could be “the foundation on which a more equal, just and humane world can be built.”

It could also be the opposite.

The availability of new forms of energy, particularly fossil fuels, has fueled human material progress in the modern era – allowing us to grow more food, manufacture and run better equipment, travel greater distances, and make our daily lives easier. The production and use of that energy has also come with huge downsides – pollution, destruction of natural landscapes, climate change, and dangers ranging from industrial accidents to car crashes to pipeline explosions – downsides that threaten the continued stability and even existence of civilization as we’ve come to know it.

This narrative – the idea that energy is a boon but that its production and use imposes harmful tradeoffs – is one that is familiar to us. It’s been the dominant narrative since the emergence of the environmental movement in the 1960s and 1970s.

But it is one that is changing. The rapid emergence of clean energy from the sun and wind (and possibly someday – but not any time soon – fusion) creates the possibility of harnessing abundant energy without the use of fossil fuels. That is not to say there are not still environmental impacts from the production and use of clean energy – often significant ones. But the impact is both qualitatively different and typically lower than the wholesale destruction caused by fossil fuel usage.

The prospect of this shift has led some observers – Klein among them – to argue that the pursuit of “energy abundance” should be a primary objective of politics, part of an overarching “abundance agenda.”

There are, however, a few problems with this. The first practical problem is that the vast majority of the energy we use still comes from polluting fossil fuels. To talk about using more energy as a goal at a time when our current energy consumption patterns are still wrecking our health and the planet is to put the cart far before the horse. Like spiking the football when you’ve just crossed the 50 yard line.

But there is a more fundamental problem with the “energy abundance” agenda. The idea that energy abundance itself can be the “foundation” of a great society is based on the assumption that using more energy is inherently better than using less. Is it?

While energy consumption delivers many benefits, it, like most things, exhibits diminishing returns. And in some circumstances, energy consumption can even be associated with negative returns.

When you stop to think about it, this is just common sense. The energy unleashed by nuclear fission can be used to power cities. It can also be used in weapons capable of laying waste to entire regions.

Beyond the use of energy for deliberately destructive purposes, even those energy-intensive systems that are designed with the intention to benefit individuals or society sometimes wind up doing the opposite.

I recently wrote about one way that society could use lots of energy and arguably make people’s lives worse off: mass adoption of flying cars. But transportation also provides an example of how already existing systems that use more energy can be – and often are – worse than systems that use less.

America’s energy-intensive transportation system leaves our cities less appealing and harms our health. Cities elsewhere in the world – such as Malaga, Spain, above – made different choices.Photo by Tony Dutzik | TPIN

Moving a lot but getting nowhere

In the years after World War II – a time when America was busy spending a large share of our unprecedented national wealth building out the world’s largest network of highways and filling them with cars – many nations around the world took a different path. Instead of bulldozing historic downtowns, many European nations took steps to preserve them. Rather than kill off rail networks and transit systems as outmoded relics of the past, governments around the world reinvested in robust, modern public transit and intercity passenger rail systems.

That’s not to say that American-style highway building wasn’t seen as desirable for a time, and emulated elsewhere in the world. As early as the 1920s, modernist architects and planners worldwide hatched radical new ideas for city design that put cars and highways front and center. Cities such as Paris developed grand highway-building schemes that would have been the envy of any American highway planner. By the 1970s, however, the costs of auto-centric transportation were becoming plainly apparent around the world, causing many (though not all) industrialized societies either to slow highway expansion or balance it with other types of transportation investments.

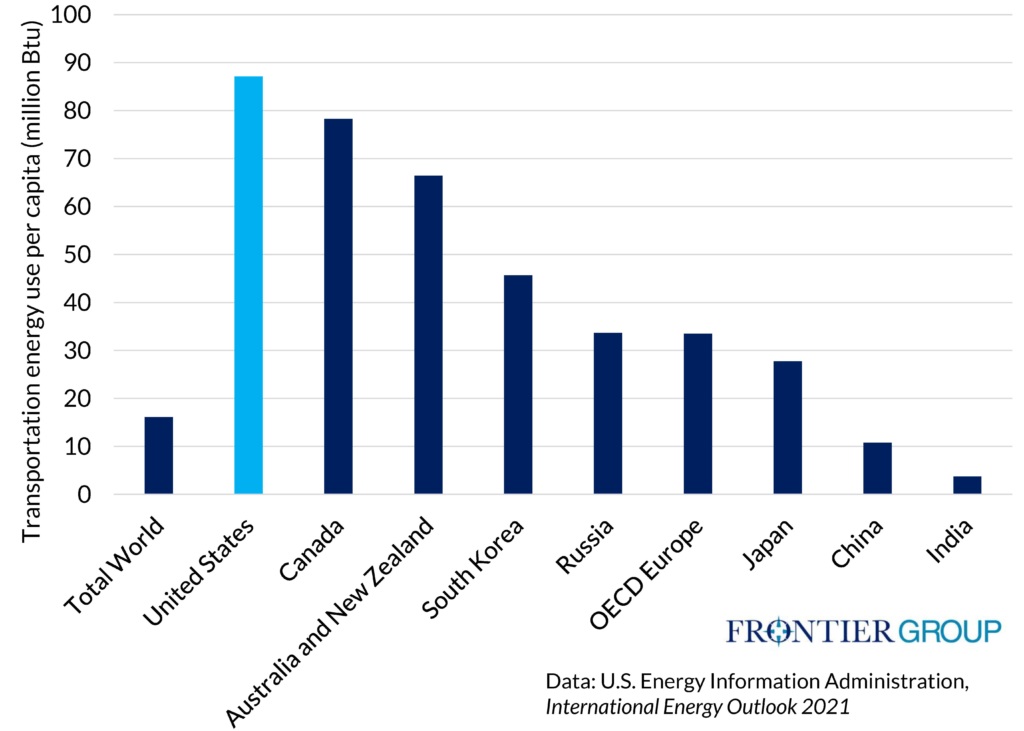

The result is a vast gap in the energy intensity of transportation in the United States versus other nations around the globe. Transportation in the United States consumes two and a half times as much energy per capita as the industrialized (OECD member) countries in Europe and three times as much as Japan. Our transportation system is 11 percent more energy intensive than that of our close cousins in Canada and 31 percent more energy intensive than the ones in similarly spread-out Australia and New Zealand.

Transportation energy use per capita (million Btu), 2019

Transportation energy consumption per capita, 2019, based on data from U.S. Energy Information Administration.Photo by Frontier Group staff | TPIN

What does all that energy consumption get us?

A recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper provides a clue. The researchers compared the accessibility of locations by car and by transit of the 109 largest U.S. and European cities. The results would not be surprising to anyone who has spent much time in U.S. and European cities – European cities were twice as accessible by transit as U.S. cities but much less accessible by car. Overall, combining transit and cars, U.S. cities had somewhat greater accessibility than European ones.

U.S.A, U.S.A., right? But the study found that there was a tremendous cost to be paid for America’s more auto-dependent transportation system. All the parking needed to support car-based mobility resulted in U.S. cities having less green space than European cities. And the car orientation of American cities was associated with more congestion, worse air pollution, more sedentary lifestyles, worse health and lower life expectancy.

Moreover, the study found, every successive expansion of transportation accessibility delivers less additional benefit – the law of diminishing returns at work. As transportation researcher David Levinson has noted previously, the first generation of Interstate highways delivered large economic benefits from added connectivity, but as the network has matured, the benefits of each additional expansion have grown smaller and smaller, to the point where, Levinson speculates, projects undertaken after the turn of the millennium may have had no net benefits at all.

America has somehow managed to build a transportation system that is more than twice as energy-intensive as our industrialized peer nations, that functions – at best – only roughly as well (and barely functions at all for those who are physically unable to drive or lack access to a car), and that leaves many of us sicker, poorer and more miserable than we might otherwise be. We would be far better off replacing some of our travel in gas-guzzling cars to denuded city centers with less-energy intensive travel on foot, by bike or on transit that connects us to healthier, more vibrant cities and towns.

The idea that energy-intensive systems can be worse than less energy-intensive ones extends beyond transportation. Anyone who has endured a cold winter in a drafty apartment knows that energy efficiency is about more than saving money or reducing pollution. Living in an energy-inefficient place is uncomfortable. Energy inefficiency is often a good indicator that a system or a product is poorly designed in other ways, and energy efficiency standards have been shown to drive not just reductions in energy use but improvements in quality as well.

What is energy, anyway?

To have a meaningful conversation about the future of energy, we need to go back to square one – to remind ourselves what energy actually is and does. The common (if oversimplified) textbook definition of energy is the “capacity to do work or create heat.” Energy moves stuff or heats stuff up. That’s it.

To link energy to societal “dynamism,” as the Niskanen Center’s Brink Lindsey does, is then, in a technical sense, correct. But there is good dynamism and bad dynamism. “Shock and awe” warfare is dynamic. Climate change is dynamic. Consumption (or, more accurately, transformation) of energy doesn’t just enable us to do (hopefully useful) work; it also creates some amount of waste and disorder as an inevitable byproduct. Entropy. If we are careful and wise, we can design systems and technologies that maximize the benefits of energy use and minimize disruption and harm. If we are not, the unintended consequences of energy use can easily overwhelm us.

There is nothing about energy abundance that inherently leads to Ezra Klein’s desired “more equal, just and humane world.” Increasing availability of fossil energy has certainly contributed to higher living standards around the world over the last century, but it has also brought with it global competition for resources that has warped our politics, fueled corruption, and led to occasional outbreaks of devastating warfare. Equality, justice and humanity? Not always so much. A future built on clean energy could be vastly better by these measures – addressing climate change alone would go a long way. But as recent research about the impact of lithium mining shows, the transition to clean energy is more likely to enhance equality, justice and humanity if it is paired with efforts to limit wasteful consumption of energy rather than further enable it.

The hard truth is that the answer to our society’s myriad problems is not more energy or less, more dynamism or less. The answer is more of the right kinds of energy applied to the right kinds of work in the right places at the right times (and less of the wrong kinds of energy applied to the wrong tasks in the wrong places at the wrong times.)

Energy is a means, not an end. No less of a light than Albert Einstein once observed that “perfection of means and confusion of goals seem – in my opinion – to characterize our age.” His words were right then. And they are right today.

To speak of energy without speaking first and foremost of the kinds of work we want that energy to do is to tempt fate. The pursuit of “energy abundance” as a goal in and of itself assumes that the means justify the ends – whatever they are. That’s backwards. Tapping the abundance of clean energy all around us can free us from a future of calamitous climate change and improve the lives of people around the world. But only if that is how we choose to use it.

Topics

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

Find Out More

Our 2024 priorities in the states

Celebrating new protections taking effect in 2024

A look back at what our unique network accomplished in 2023