Fixing the Trump-era rollbacks to the Endangered Species Act

Out of the gates, here’s what President Biden did for America’s wildlife.

Wildlife in the United States and around the globe is in peril. The UN biodiversity conference warns that one million species are at risk of extinction. There are 3 billion fewer birds in the skies in North American than in 1970, and scientists project that up to 30% of America’s wildlife species are at risk of extinction within decades.

The situation is dire, but on January 20th we got some good news.

On his first day, President Joe Biden signed a string of executive orders to roll back some of the previous administration’s worst attacks on the environment. In a move that may have been overshadowed by rejoining the Paris Climate accord and blocking the Keystone XL pipeline, Pres. Biden put up for review eight actions by the last administration that had scaled back the Endangered Species Act, which has for decades been one of our most effective environmental laws, with an incredible track record at preventing extinction.

If you want to dig deeper, here is a breakdown of each of those rollbacks:

1. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Revised Designation of Critical Habitat for the Northern Owl,” 86 Fed. Reg. 4820 (January 15, 2021).

This rule, finalized in the last week of the Trump administration, reduces critical habitat protections for northern spotted owls by 3.4 million acres — an area nearly the size of Connecticut. Critical habitat protections have been key to the conservation of the owls as well as old growth forests that northern spotted owls need to survive.

,

,

2. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Regulations for Designating Critical Habitat, 85 Fed. Reg. 82376 (December 18, 2020).

This rule mandates that the Fish and Wildlife Service consider the economic impacts and vaguely defined “community impacts” of protecting critical habitat in certain areas, based in part on the speculative valuation of industry experts. In other words, this rule essentially puts a thumb on the scale in favor of developers looking to block habitat protections for endangered species. And as the name suggests, critical habitat protections really are an essential part of why the Endangered Species Act works; species can only survive and thrive when they are in their habitat.

3. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-Month Finding for the Monarch Butterfly,” 85 Fed. Reg. 81813 (December 17, 2020).

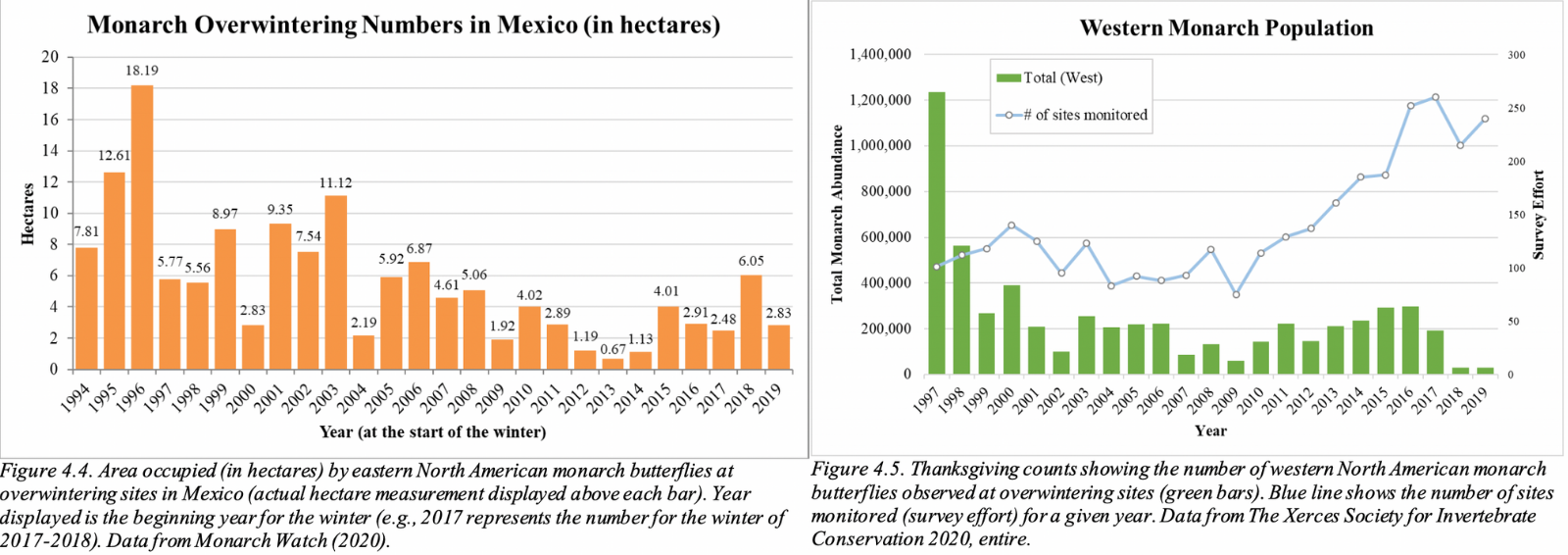

This rule, perplexingly, acknowledges that the status of monarch butterflies warrants listing under the Endangered Species Act, but finds that listing of the butterflies is “precluded by work on higher priority listing actions.” Basically, the former administration argued that it didn’t have the resources to protect these butterflies, even though the science merits their protection. Our take? Extinction is forever and the monarch needs protections quickly, as this butterfly species has seen a dramatic decline over the past several decades.

Chart from U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

4. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Regulations for Listing Endangered and Threatened Species and Designating Critical Habitat,” 85 Fed. Reg. 81411 (December 16, 2020).

This rule redefines “critical habitat” so that protections will only exist for places where a species lives today or for areas that, if unchanged, could host the species. The shifting of this definition means that locations that could one day become habitat, or that could be restored to become a suitable habitat, wouldn’t be protected.

Many endangered species occupy only a tiny fraction of their former range and need much larger areas — often outside their current habitat — in order to survive and thrive in the long term. As the climate changes, it’s essential that we protect certain areas so species can shift their range in response. This rule will undermine those efforts.

5. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Eleven Species Not Warranted for Listing as Endangered or Threatened Species,” 85 Fed. Reg. 78029 (December 3, 2020).

This rule determined that it is not warranted at this time to list 11 species, including: the Doll’s daisy; Puget Oregonian; Rocky Mountain monkeyflower; southern white-tailed ptarmigan; tidewater amphipod; tufted puffin; Hamlin Valley pyrg; longitudinal gland pyrg; sub-globose snake pyrg; the Johnson Springs Wetland Complex population of relict dace; and the Clear Lake hitch. Some of these decisions not to list could be warranted due to species recovery. But Biden’s review will make sure that none of these species still need protection.

6. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Removing the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife,” 85 Fed. Reg 69778 (November 3, 2020).

This rule delists the gray wolf from federal protection under the Endangered Species Act, leaving their stewardship to the states. Once common throughout much of the lower 48 states, then nearly erased from all of them, gray wolves were an early success story for the Endangered Species Act. Thanks to reintroduction efforts in central Idaho and Yellowstone National Park in the 1990s, there are now roughly 6,000 wolves in the continental U.S.

But when the wolves were delisted in 2011 in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan for a three-year window, an estimated 1,500 individuals from this keystone species were killed before protections were restored. To repeat this mistake would be devastating to the gray wolves in the lower 48.

7. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Regulations for Listing Species and Designating Critical Habitat,” 84 Fed. Reg. 45020 (August 27, 2019).

This new rule makes it easier to remove a species from Endangered Species Act protections. Additionally, it raises the standard for how imminent a risk must be for a species to qualify as a threatened species — an especially problematic change for species at risk of climate disruption. The rule mandates that the secretary of commerce or interior can only designate an unoccupied area as critical habitat if:

a) protecting all areas currently occupied by the species would be insufficient

b) the unoccupied area currently has biological features that are essential for the conservation of the species.

Essentially, this rule is a three-pronged attack on the ESA: it makes it harder for species to get protected, easier for those protections to be removed, and it waters down the value of those protections.

8. “Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Regulations for Interagency Cooperation,” 84 Fed. Reg. 44976 (August 27, 2019).

The Endangered Species Act requires that government agencies confer with the Departments of Interior or Department of Commerce if any agency action might harm a threatened or endangered species. This rule makes a number of technical changes that lessen the requirements for other agencies when consulting with DOI/DOC, and lowers the standard for what would be considered harmful. Basically, other government agencies don’t have to be as careful about avoiding harm to an endangered species.

There’s at least one other Trump rollback of the Endangered Species Act that needs to be fixed.

We are hopeful that the Biden administration will reinstate a longstanding policy that both Republican and Democratic administration’s had followed for decades before it was rescinded in 2019. The “blanket rule,” as some call it, mandates that when a species is newly classified as threatened, it automatically starts with the same protections dedicated to an endangered species, unless a review determines otherwise. Under Trump, this standard went away. The new process at best delays and at worst reduces protections for threatened species.

Undoing the last four years of attacks on the ESA is the first necessary step to fixing the biodiversity crisis. But we can’t stop there. Other conservation measures will be needed, but it’s good to see Pres. Biden’s strong start.

Top photo by Gregory “Slobirdr” Smith / Flickr

Topics

Authors

Alex Petersen

Find Out More

Why environmentalism is conservative

Bank of America said it would stop financing drilling in the Arctic Refuge. Now it’s backtracking.

Endangered species can’t wait for protection