When the personal becomes political

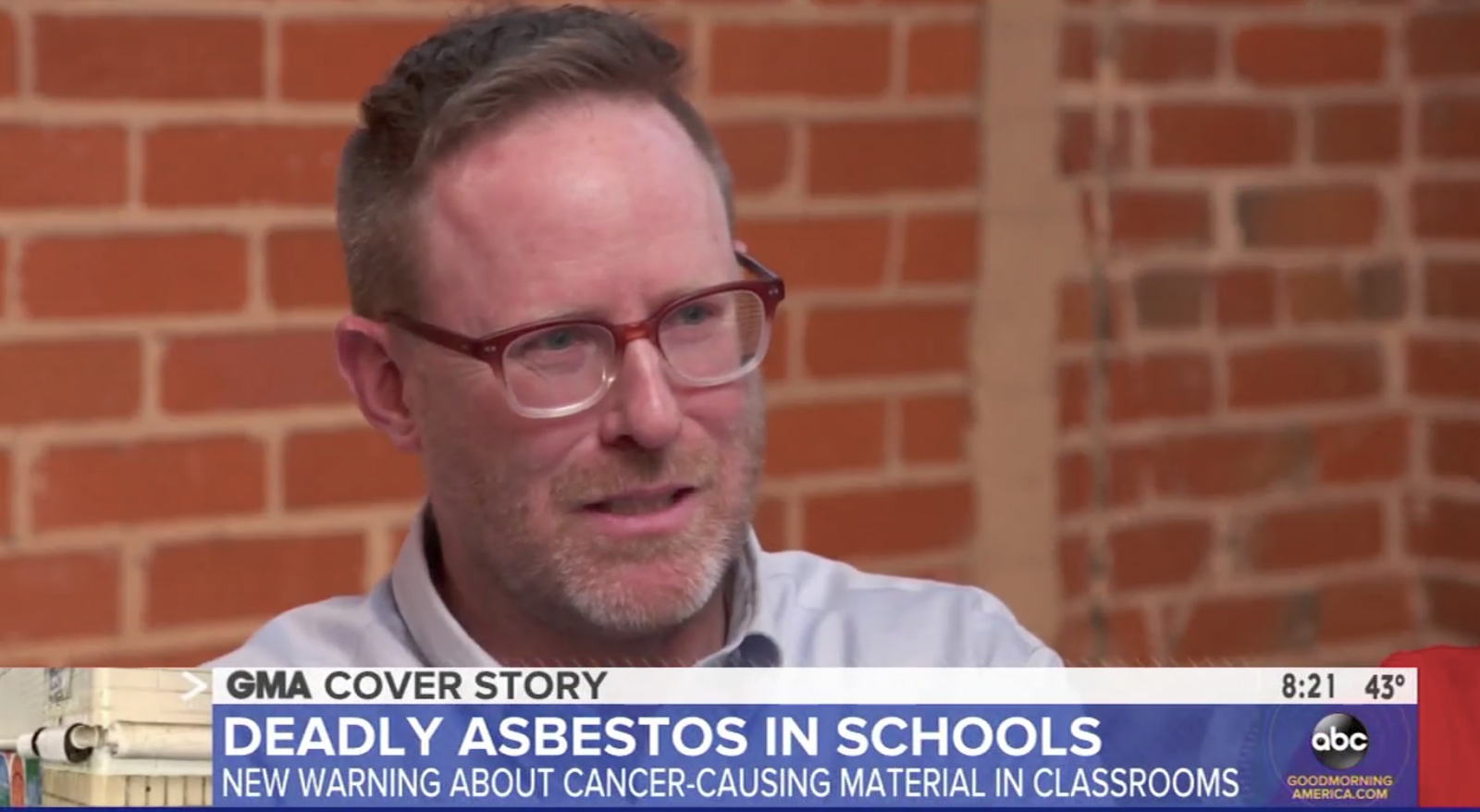

For David Masur, being interviewed on television isn’t anything new.

As executive director of PennEnvironment, a Public Interest Network organization, he’s been on the nightly news many times, speaking about everything from fracking to conservation.

On Nov. 21, however, David was featured on a Good Morning America segment, not as an environmental advocate, but as a parent. His two children, Owen and Evie, ages nine and six, both attend Philadelphia’s Southwark Elementary School. Recently, a teacher at a nearby school was diagnosed with mesothelioma, a disease linked to asbestos exposure.

David started down the path that led to Good Morning America three years ago. Working on PennEnvironment’s Get the Lead Out campaign, he reached out to an environmental scientist, Jerry Roseman, with the Philadelphia teachers’ union. One day, Jerry told David that, while it was great that they were making progress on lead in schools’ drinking water, that problem was just the tip of the iceberg of health threats in Philly schools. As Jerry later told reporters, “I have a searing image in my mind of a child who has his arm around an asbestos-covered pipe in a gym and he’s sucking his thumb. That’s a problem.”

One thing led to another, and soon Jerry and David started the Philadelphia Healthy Schools Initiative. We interviewed David on being both advocate and parent on his work on the Healthy Schools Initiative in Philadelphia. Here’s a transcript of that conversation:

What was your immediate reaction to learning of the health risks in Philadelphia-area schools?

PennEnvironment was already working on lead in drinking water, so I wasn’t exactly surprised that there were other district-wide contaminants. What shocked me was how dangerous the overall levels really were, and just how bad some of the overall conditions were. We’d find schools that would have only one working toilet for hundreds of students; classrooms with no heat and kids sitting in classrooms all day with hats, coats and mittens on, trying to learn; still water sitting on bathroom floors; levels of asbestos contamination thousands of times higher than considered safe. It’s jarring, and immediately makes you frightened and angry, especially having kids in the schools.

Outside of your role as executive director of PennEnvironment, how else have you advocated for safer schools?

After working with Jerry and parent groups, labor union representatives, student groups and others to convince the city of Philadelphia to pass some of the strongest reporting and testing requirements for lead in school drinking water in the nation, we sat down and said, ‘That worked really well, and we won! And we like each other and the new partners we’re working with and the relationships we’ve built. Let’s stick together … and tackle some of the other environmental health issues out there!’ That became the starting point for the Philly Healthy Schools Initiative in 2017. We came up with a platform and policy priorities, developed our case-for and problem statements, and recruited other partners that we needed at the table to make the coalition work and be representative of the stakeholders in the process.

How do you see your roles as parent and professional advocate as complementing each other?

As the PennEnvironment director, I bring the organization’s strategic insights, knowledge of the political process and players, and campaign planning to the table. As a parent, I can tell decision-makers what I’m seeing and experiencing in my own kids’ schools and what I hear from teachers and other parents. It also really helps to relate to, and work with, other parents, teachers and principals across the city when they know that my kids are in a school with the same threats. It puts us all on the same level — at the end of the day, we’re all parents trying to fight the good fight together.

It seems like there is a wide range of people involved in the coalition. Can you tell me more about that, and how you think it has made the initiative stronger?

The diversity of the coalition fits our general organizing strategy at TPIN: There is power in broad-based support. It’s important for decision-makers to see that our issues aren’t just issues that environmental groups care about. A good example is the support we have from the president of the Philly AFL-CIO, Pat Eiding. Before being head of one of the most powerful AFL affiliates in the nation, Pat worked for 25 years as a union member in the Insulators and Asbestos Workers union. So he knows asbestos first-hand. Pat always tells a story at news conferences about how he went back to visit the Philly school he attended as a child, and there was scaffolding everywhere inside the school, bricks falling out of the walls of the school — an overall unsafe place for kids — and how angry he was to see this place that he once took pride in, now in such disrepair and a risk to kids and teachers.

How does the initiative fit PennEnvironment’s mission for Pennsylvania?

Working on this issue helped us build stronger coalitions and relationships, raise grant money, recruit volunteers, garner media attention, and build relationships with the city’s elected officials. So it’s had a lot of benefits, even as it’s a good example of the tensions we face when picking issues.

Topics

Find Out More

Celebrating new protections taking effect in 2024

What’s the problem with fast fashion?