Food for thought: Are your groceries safe?

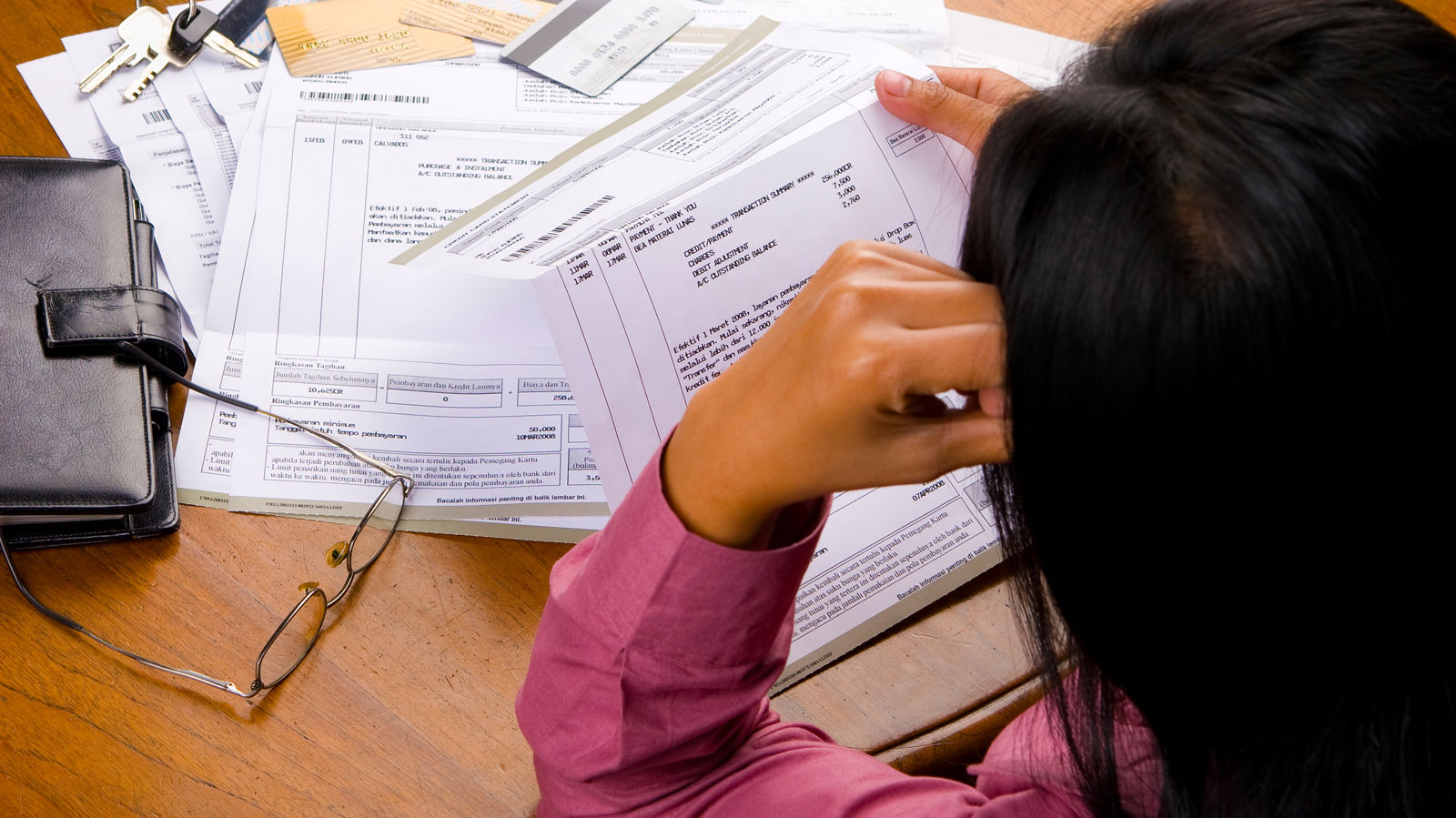

When you have hundreds or even thousands of people getting sick every year from food - many after recalls are announced, you have a problem. Part of the solution is grocery stores. We contacted 50 of the largest grocery and convenience store chains to learn how they get the word out to customers about food recalls. Some take several steps. Some do very little.

You remember last year’s big onion recall because of an outbreak of Salmonella. Looking back, it’s an infuriating example of how our country’s food recall system often doesn’t work well. Ultimately, more than 1,000 people got sick. One-fourth of them were hospitalized.

On Oct. 21, 2021, the Food and Drug Administration said it and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with state and local partners, were investigating an outbreak of Salmonella infections linked to whole, fresh onions and identified ProSource Produce LLC of Hailey, Idaho as a source of potentially contaminated onions imported from Chihuahua, Mexico. The day before, ProSource had announced a voluntary recall. The onions had been distributed in 35 states, to retail stores, wholesalers and restaurants and other foodservice customers.

The next day, Oct. 22, the FDA said its investigation identified Keeler Family Farms as an additional supplier of onions from Chihuahua, Mexico, for many of the restaurants where sick people reported eating. Keeler also agreed to a voluntary recall of onions imported during July and August 2021.

By Oct. 29, the CDC reported 808 illnesses across 37 states and Puerto Rico, mostly gastro-intestinal illnesses. By Nov. 12, 2021 the CDC reported 892 illnesses.

On Feb. 2, 2022, the CDC said the outbreak was over. It tallied 1,040 illnesses in 39 states, plus Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico. Among those, 260 people were hospitalized. Fortunately, no one died. As it turns out, the first illness connected to the outbreak was reported May 31, 2021, nearly five months before the first recall. Investigators rely on genome sequencing technology to connect pathogens from sick patients and then trace them to a food.

The CDC said the last illness onset was Jan. 1, 2022, two months after the last recall. The incubation period for salmonellosis is generally 12 to 72 hours.

How many of those illnesses and hospitalizations could have been prevented through a more efficient food recall system that notifies consumers more quickly?

“I have no idea why it takes that long. It’s a black box,” Dr. Ben Chapman, a professor and food safety specialist in the Department of Agricultural and Human Sciences at North Carolina State University, said in an interview with U.S. PIRG Education Fund. “We have an inconsistent, fragmented system. No one really owns recalls.”

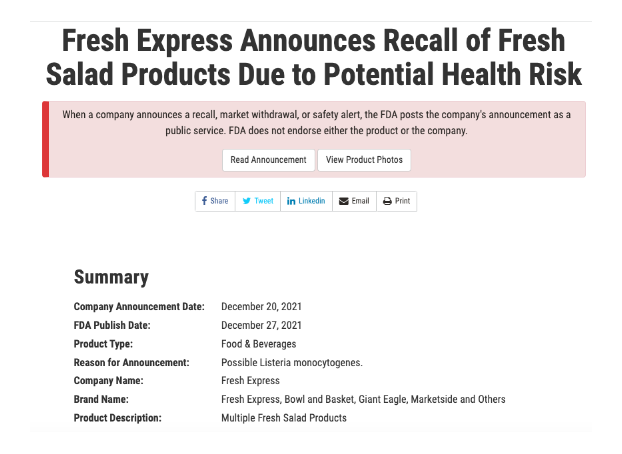

Then there was the Dole lettuce recall right before Christmas. The first announcements from the FDA and Dole came on Dec. 22, 2021. The CDC investigation later showed the first illness connected to this was actually reported seven years earlier, on Aug. 16, 2014. The last illness was reported on Jan. 15, 2022, more than three weeks after the initial recall was announced. Listeria can cause serious and sometimes fatal infections in young children, elderly people and others with weakened immune systems. Listeria infection can cause miscarriages and stillbirths in pregnant women.

The outbreak ultimately infected 18 people; 16 were hospitalized. Three people died: one each in Ohio, Michigan and Wisconsin.

These two major recalls from the last seven months showcase the weaknesses in our food recall system:

It often takes too long for companies and regulators to notify grocers, consumers, restaurants and food packagers, particularly regarding Class I recalls. These recalls are ones where the FDA says there is a “reasonable probability” that exposure or use of the product could cause “serious adverse health consequences or death.”

And once grocers find out, they aren’t required to contact customers who may have already purchased contaminated products. While many stores do quickly notify customers one way or another, the practices aren’t uniform and aren’t always timely. Meanwhile, people continue to get sick.

The CDC estimates that one in six Americans become ill every year from foodborne diseases. Among those, 128,000 wind up in the hospital and 3,000 die. Those illnesses are just the ones that regulators find out about. The CDC says most people who get some type of mild stomach bug that could be food poisoning don’t seek medical care or report their case for investigation.

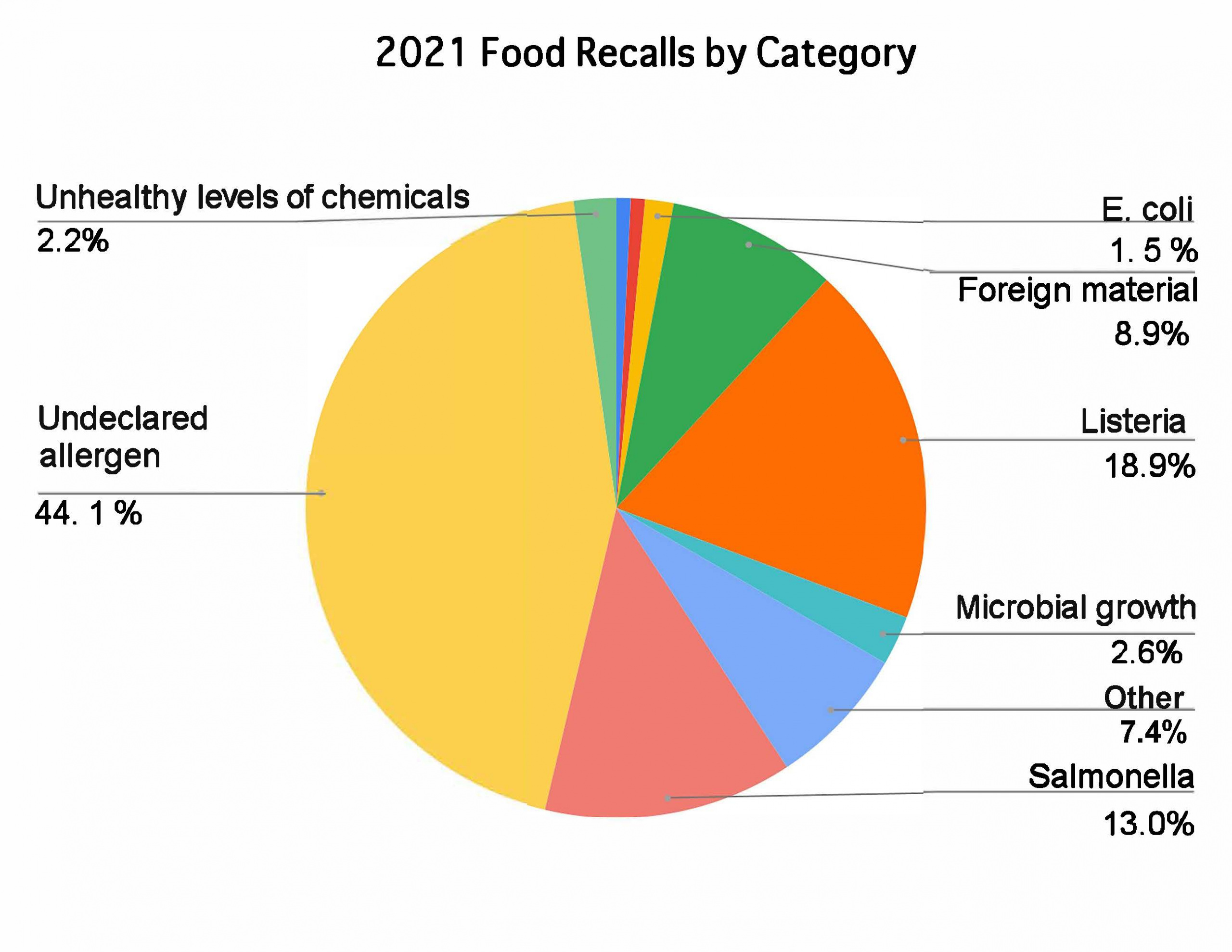

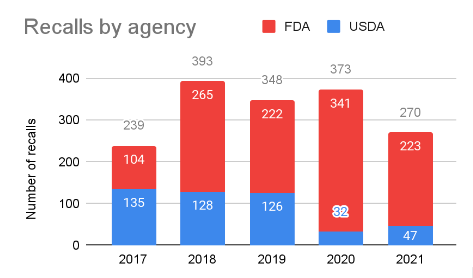

Last year there were 270 food and beverage recalls from the FDA and U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA FSIS). For the last five years, the average has been 325 recalls a year. For the last four years, the overwhelming majority have come from the FDA.

Clearly, a goal of our food production and distribution system must be reducing the need for recalls in the first place. That’s the difficult part. This report looks at the easier part – the logjams once the need for a recall is identified and how grocers and other retailers notify customers who may have a contaminated product in their home.

We contacted 50 of the largest grocery and convenience store chains to learn how they get the word out to customers. Some take several steps. Some do very little.

(See a list of the 50 stores and what they do in the appendix of our report.)

Fortunately, many retailers already knew and were pulling products from their shelves and notifying customers in some cases.

TYPES OF NOTIFICATIONS

Tell the FDA to do more to alert people to food recalls

Topics

Authors

Teresa Murray

Consumer Watchdog, PIRG

Teresa directs the Consumer Watchdog office, which looks out for consumers’ health, safety and financial security. Previously, she worked as a journalist covering consumer issues and personal finance for two decades for Ohio’s largest daily newspaper. She received dozens of state and national journalism awards, including Best Columnist in Ohio, a National Headliner Award for coverage of the 2008-09 financial crisis, and a journalism public service award for exposing improper billing practices by Verizon that affected 15 million customers nationwide. Teresa and her husband live in Greater Cleveland and have two sons. She enjoys biking, house projects and music, and serves on her church missions team and stewardship board.

Find Out More

How Mastercard sells its ‘gold mine’ of transaction data

Medical Bills: Everything you need to know about your rights

How printers keep us hooked on expensive ink